Governor Publicly Announces Commutation of Sentence for Spolin Law Client, Which He Did by Himself

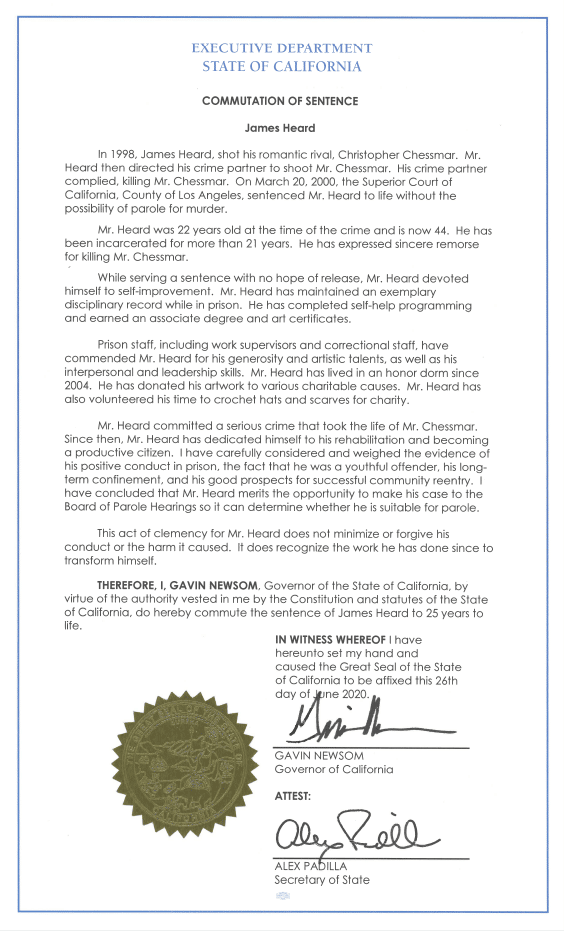

Published on July 14, 2020California Governor Gavin Newsom has announced the commutation (reduction) of sentence for a Spolin Law client who was previously serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. The decision was announced on June 26, 2020. A copy of the commutation, signed by Governor Newsom as well as Secretary of State Alex Padilla, was released to state and national media outlets shortly after the commutation.

The Spolin Law client’s commutation was signed by Governor Gavin Newsom and Secretary of State Alex Padilla

A commutation of sentence is a method that state governors can use to cut short a person’s sentence. It is often used when someone has received an overly harsh sentence or has shown rehabilitation during his or her time in prison. A governor’s commutation is similar to the more well-known governor’s pardon. While a pardon erases a criminal conviction completely, a commutation simply cuts short the person’s sentence. State governors can commute or pardon for state crimes; the President can commute or pardon for federal crimes.

Governor Newsom explained his decision to commute the client’s sentence by describing the client’s excellent behavior, educational program participation, various certificates, and other noteworthy aspects of the client’s life.

In his commutation announcement, Governor Newsom said the following:

In 1998, James Heard, shot his romantic rival, Christopher Chessmar. Mr. Heard then directed his crime partner to shoot Mr. Chessmar. His crime partner complied, killing Mr. Chessmar. On March 20, 2000, the Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles, sentenced Mr. Heard to life without the possibility of parole for murder.

Mr. Heard was 22 years old at the time of the crime and is now 44. He has been incarcerated for more than 21 years. He has expressed sincere remorse for killing Mr. Chessmar.

While serving a sentence with no hope of release, Mr. Heard devoted himself to self-improvement. Mr. Heard has maintained an exemplary disciplinary record while in prison. He has completed self-help programming and earned an associate degree and art certificates.

Prison staff, including work supervisors and correctional staff, have commended Mr. Heard for his generosity and artistic talents, as well as his interpersonal and leadership skills. Mr. Heard has lived in an honor dorm since 2004. He has donated his artwork to various charitable causes. Mr. Heard has also volunteered his time to crochet hats and scarves for charity.

Mr. Heard committed a serious crime that took the life of Mr. Chessmar. Since then, Mr. Heard has dedicated himself to his rehabilitation and becoming a productive citizen. I have carefully considered and weighed the evidence of his positive conduct in prison, the fact that he was a youthful offender, his longterm confinement, and his good prospects for successful community reentry. I have concluded that Mr. Heard merits the opportunity to make his case to the Board of Parole Hearings so it can determine whether he is suitable for parole.

This act of clemency for Mr. Heard does not minimize or forgive his conduct or the harm it caused. It does recognize the work he has done since to transform himself.

The client’s family was extremely happy to hear this good news.

To learn more about commutations and other types of post-conviction relief, call one of the Spolin Law attorneys or staff members at (866) 716-2805. Please also note that Spolin Law was not the law firm involved in the Application for Commutation of Sentence for this client. This post is intended to celebrate the client’s win, which he achieved without our assistance on this matter.

New York legislators take action against police brutality by proposing a new bill to ban the chokehold

Published on July 9, 2020Pressured by the public protests demanding justice for George Floyd, New York legislators have just passed a bill that will ban the use of chokeholds by law enforcement. Although only recently adopted, this revolutionary bill originated in 2014 just after 43-year-old Eric Garner was strangled to death by four New York police officers.

In a peaceful arrest that quickly turned violent, Staten Island local, Eric Garner, was killed by NYPD officers on July 17, 2014. Being suspected of selling loose, untaxed cigarettes, Garner was approached by four police officers who proceeded to forcefully push him to the ground and hold him in a chokehold for around 15 seconds. In a disturbing video that recorded the incident, Garner was seen flailing his arms and gasping for air as he urgently repeats the phrase, “I can’t breathe,” a total of 11 times. Just moments later, Garner lost consciousness and died.

The NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who was responsible for Garner’s death, was fired from his job, but was never criminally prosecuted for his crimes.

In 2015, a year after Garner’s murder, New York Assemblyman Walter Mosley proposed a bill to New York Legislators in hopes of banning the use of the chokehold by New York Police officers. However, with little support behind it, the bill was abandoned and never signed into law.

Nevertheless, overwhelming pressure from the public over George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis pushed New York Legislators to revive the bill. Sponsored once again by Assemblyman Mosley, the bill, later named the Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act in honor of Garner, was finally put to a vote in June of 2020, almost 5 years after its original proposal.

On Monday, June 8, the bill was passed by both the New York Assembly and Senate by a vote of 140-three. Just four days later on Friday, June 11th, New York State Governor Andrew M. Cuomo signed the Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act into law.

The Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act states that the use of a chokehold or any other similar restraint that restricts breathing is considered a class C felony and is punishable by up to 15 years in prison.

Chokeholds have been prohibited in New York since 1993, however according to Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, “The NYPD ban on chokeholds was not enough to protect Eric Garner, and it is not enough today. This legislation will put an end to the practice across the state.” With these new, stricter laws that now make the use of a chokehold a state crime, Heastie and other assembly members hope to prevent such horrible incidents from ever happening again.

The Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act was not the only bill signed into law by Governor Cuomo on Friday. In addition to banning the chokehold, New York legislators passed bills that require police disciplinary records be made public, prohibit race-based 911 calls, and force state police officers to wear body cameras.

These are just a few of the bills included in a new police reform bill package proposed by New York Legislators following the nationwide George Floyd protests. Cuomo has signed only four of the proposed 10 bills. The remaining six bills still await his signature.

At the bills’ public signing, Governor Cuomo made a statement explaining his motivation behind approving them saying, “Police reform is long overdue.” The governor said that these bills aren’t just about George Floyd’s murder, but about the “long list” of African American citizens who too have fallen victim to police brutality. Cuomo thinks that the implementation of these new bills will bring the state of New York one step closer towards ending the “injustices against minorities in America by the criminal justice system.”

This sweeping reform in New York has inspired other states to establish similar policies. In states like California, Chicago, Denver, Florida, Minneapolis and Phoenix, county police departments have announced that they will suspend the use of the chokehold, and the just as dangerous carotid restraint. Across the globe in France, the French government announced that it too is banning law enforcement officials from using chokeholds.

The passing of the Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act will bring necessary change that New York politicians and citizens have been waiting for. Assembly member and sponsor of the bill, Walter Mosley expressed his enthusiasm in front of the New York State Assembly saying, “In 2015 I introduced this bill to outlaw chokeholds statewide, and I am proud to see it taken up today as we pass legislation to reform our criminal justice system.”

Although Mosley is glad to have achieved such a feat, he thinks there is much more to be done in order to finally put an end to police brutality. He said, “This is an important step forward, but it will not be the last. We must work to change the way that police officers interact with communities of color, or we will continue to see these killings occur.”

If you are in need of legal help in New York, please contact Spolin Law, P.C.

Supreme Court Sends Death Penalty Case Back for Reconsideration Of Ineffective Assistance of Counsel Claim

Published on— But Skips Its Chance to Modify Prejudice Prong of Strickland

In a 5-3 per curiam decision, the United States Supreme Court stopped short of doing what the habeas corpus petitioner asked it to do: modify or overrule the prejudice prong of Strickland v. Washington (1984), 466 U.S. 668, in the review of a claim of ineffective assistance of trial counsel. However, a majority of the Court in Andrus v. Texas (2020), 590 U.S. ___, found that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals’ one-sentence dismissal of Andrus’s claim “without elaboration” was insufficient to support a determination that no prejudice occurred. It remanded the case for reconsideration of that issue.

Andrus was convicted of the murders of two people during a bungled carjacking. Trial counsel put on no defense during the guilt phase of the trial, opting instead to focus on the penalty phase. However, trial counsel failed to investigate the existence of mitigating evidence. He failed to present readily available evidence that Andrus’s mother was a drug addict, drug dealer, and prostitute who sold and used drugs around her children. She would disappear for days, sometimes weeks, at a time, on her drug binges. Andrus was often left with the responsibility to raise his siblings. His mother brought home abusive boyfriends who were in and out of Andrus’s life. At age 10 or 11, he was diagnosed with affective psychosis.

At age 16, Andrus confined in a Texas juvenile detention center for serving as lookout while his friends robbed a woman of her purse. He was put on high doses of psychotropic drugs and served long stints of solitary confinement. On multiple occasions, he self-harmed and threatened suicide. He was transferred to an adult facility and released at age 18. Not long after, he committed the murders of which he was convicted. In prison, Andrus attempted suicide.

None of the foregoing evidence was presented during the penalty phase of Andrus’s trial. In fact, trial counsel was unaware of the evidence because he did not investigate Andrus’s past and failed to interview witnesses who could have testified to those facts. The only witnesses that trial counsel did present actually bolstered the prosecution’s case that Andrus had a propensity for violence and was a threat to those around him. Andrus was sentenced to death.

After an unsuccessful direct appeal, Andrus filed a petition for habeas corpus in the trial court, claiming ineffective assistance of trial counsel in violation of his Sixth Amendment right. After an eight-day hearing, at which the above evidence of Andrus’s past was introduced, the trial court concluded that trial counsel had been ineffective and that such ineffective representation prejudiced Andrus.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reversed. The court concluded that Andrus had failed to show, as he was required to do under Strickland, that counsel’s representation “fell below an objective standard of reasonableness” or that there was a “reasonable probability that the result [of the penalty phase of the trial] would have been different” had counsel’s performance not been deficient. Andrus petitioned the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari.

In the Supreme Court, Andrus argued that the abbreviated analysis of Strickland by Texas courts in general and by the court in his case in particular resulted in the pro forma rejection of meritorious ineffective-assistance-of-counsel cases. He claimed that in cases such as his, where counsel’s trial performance was patently deficient, the “truncated, analytically unsound” application of the second prong of Strickland produces unjust results. The prejudice prong is so onerous, he claimed, that few courts find it satisfied, and he questioned how a criminal defendant could fail to obtain habeas relief when the adversarial system had so utterly failed.

Claiming that an abbreviated Strickland analysis that looks only at the evidence adduced at trial to determine prejudice is unjust and unconstitutional, Andrus argued that a court must compare the evidence from the trial with the evidence from the habeas corpus hearing to determine whether the defendant was prejudiced. The question is whether the new evidence adduced at the habeas corpus hearing would have affected the outcome of the trial, not whether the evidence at trial was sufficient to support the penalty imposed. Further, Andrus claimed that a reviewing court in a habeas corpus ineffective assistance claim must assess how the deficit performance affected the fundamental fairness of the proceeding.

The Supreme Court did not bite on the opportunity to modify or overrule Strickland. Without addressing Andrus’s arguments on that score, the Court applied the Strickland test to his claim. It did, however, reject the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals’ decision dismissing the habeas corpus petition. Disagreeing with the Texas court, the Supreme Court held that the record clearly showed that the counsel’s conduct fell below reasonably objective standards for representation.

Next, the Court stated that the Texas court “may have failed properly to engage with” the question of prejudice from that ineffective representation. The lower court “concluded without elaboration” that Andrus failed to meet the Strickland standard, but it should have considered “the totality of the mitigation evidence” — both that adduced at trial and that presented in the habeas hearing in the trial court. That evidence, the Supreme Court held, must be reweighed against the evidence in aggravation to determine whether a reasonable probability exists that Andrus would have received a different sentence. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals’ opinion was “unclear” as to whether it engaged in this analysis, and the Supreme Court remanded the case for further consideration of the prejudice issue.

While the Supreme Court did not modify or overrule the prejudice prong of